Cabaret Voltaire – Geburtsort von Dada in Zürich

Ein Überblick von Laura Sabel (DE/ENGL)

Deutsch

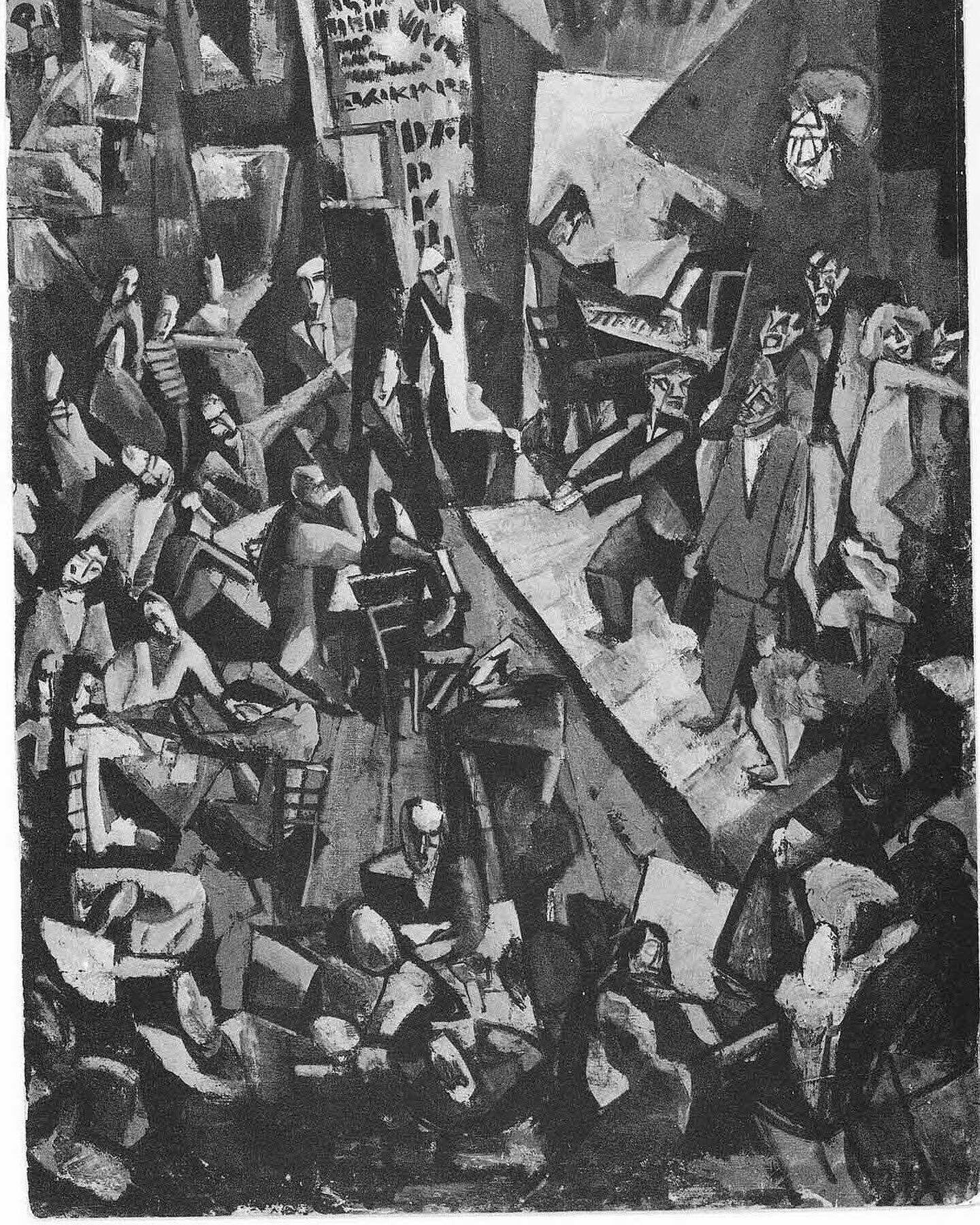

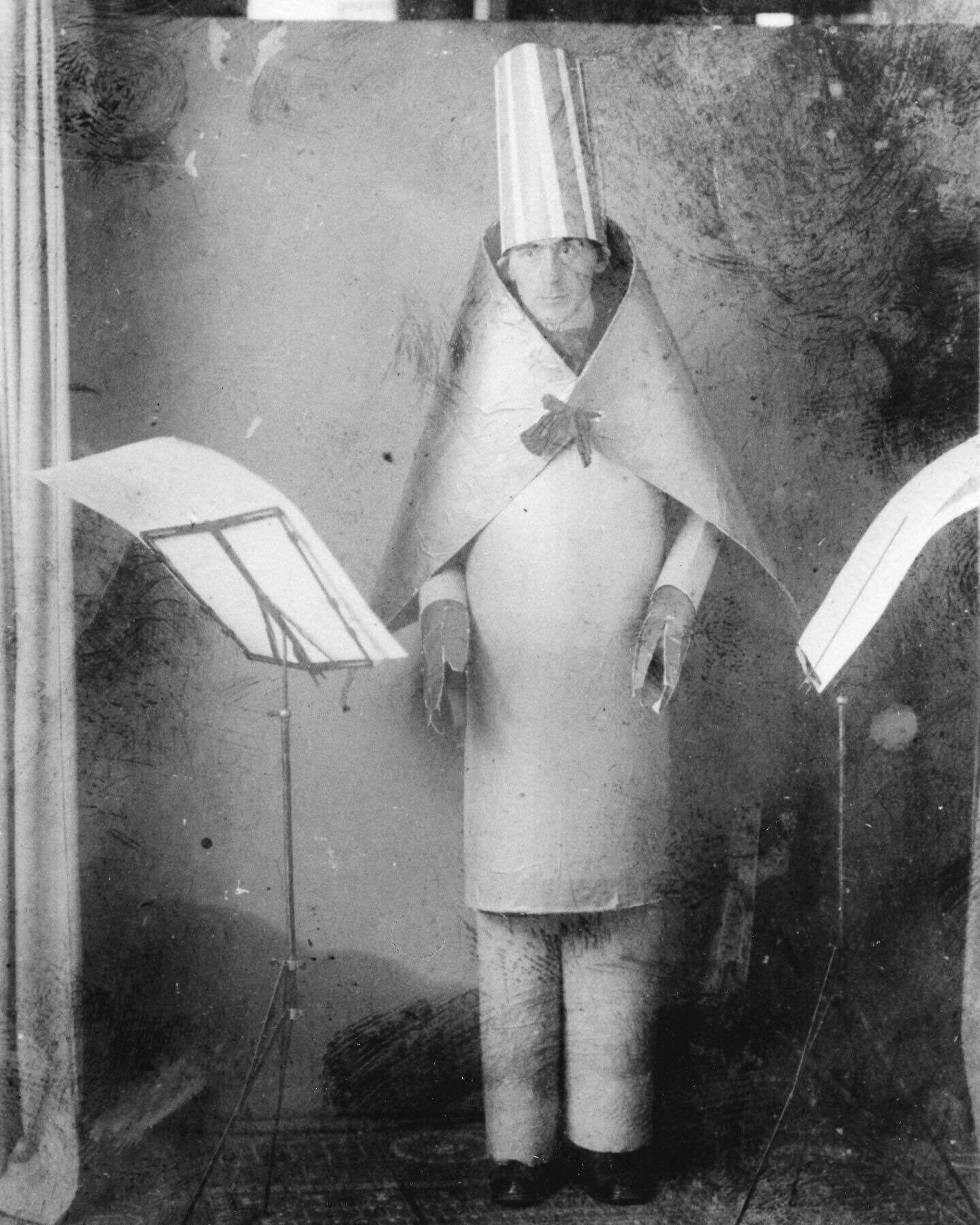

Das Cabaret Voltaire ist der Geburtsort von Dada und wurde am Abend des 5. Februar 1916 in Zürich gegründet. Hier begann die Geschichte der avantgardistischen Kunstbewegung, die nicht nur die europäische Moderne, sondern auch die Kunst und Gesellschaft von heute massgeblich prägte. Als das Cabaret Voltaire – zunächst als Künstlerkneipe Voltaire – eröffnete, befand sich Europa bereits zwei Jahre im Krieg und erlebte einen Bruch im wirtschaftlichen Aufschwung und Wachstum, die durch koloniale Eroberungen sowie die industrielle Revolution bedingt waren. Während der Erste Weltkrieg wütete, suchten viele Intellektuelle, Schriftsteller*innen, Anarchist*innen, Künstler*innen und Oppositionelle Zuflucht in der «neutralen» Schweiz. Aus dem Exil heraus richteten sie ihren Protest gegen das politische Klima und das herrschende System und fanden Orte, an denen sie sich austauschen und verbünden konnten. Da der Wohnraum in Zürich aufgrund von steigenden Einwanderungszahlen knapp war, spielte sich das Leben mehrheitlich in Kaffeehäusern, Varietés und Cabarets ab, die zu dieser Zeit eine Hochkonjunktur erlebten. Das Niederdorf war das ehemalige Rotlichtviertel und Ort der Unterhaltung in Zürich. Als Emmy Hennings und Hugo Ball im Mai 1915 in Zürich eintrafen, waren sie zunächst in unterschiedlichen Varietés tätig, zuletzt im Cabaret Hirschen, wo Ball als Pianist auftrat und Hennings als erfahrene Diseuse sang und tanzte. Der Theatermacher Ball wollte schon bald sein eigenes Cabaret gründen und bat den Wirt Jan Ephraim, ihm das Hinterzimmer seiner Meierei das sogenannte «Holländerstübli» zu vermieten. Es sollte ein internationales Cabaret entstehen, ein Ort der künstlerischen Unterhaltung und des geistigen Austauschs, dessen Bühne für alle offen war. Für den Eröffnungsabend baten Hennings und Ball ihre Bekannte in und ausserhalb der Schweiz künstlerische Arbeiten beizusteuern, sodass sie eine kleine Ausstellung mit dem Kabarett verbinden konnten. Und so kamen am 5. Februar Sophie Taeuber und Hans Arp, der zuvor die Decke blau und Wände schwarz bemalt hatte und neben seinen eigenen Arbeiten auch einige von Picasso, Arthur Segal und Otto van Rees zur Verfügung stellte. Tristan Tzara, der rumänische Verse rezitierte, kam zusammen mit Marcel Janco, der seinen Erzengel aufhängte, Hennings sang auf der aus Brettern genagelten Bühne einige Chansons und ein Balalaika-Orchester spielte russische Volkslieder. Das Publikum sass im überfüllten Raum an rot eingedeckten Tischen und war durch einen dürftigen grünen Vorhang von der Bühne getrennt. Von dem Tag der Eröffnung bis zur Schliessung des Cabaret Voltaire im Juli 1916 fanden allabendlich – ausser freitags – Soireen statt, die aus musikalischen, theatralischen und tänzerischen Darbietungen aller Art sowie aus Rezitationen von Texten und Gedichten bestanden. Ausserdem wurden thematische Abende veranstaltet, darunter eine russische, französische und eine schweizerische Soiree. Richard Hasenbeck konnte erst am 26. Februar nach Zürich kommen und wollte mit seiner aus heutiger Sicht problematischen sogenannten «N*trommel» die Literatur in Grund und Boden trommeln. Am 18. April 1916 erwähnt Ball in seinem Tagebuch Die Flucht aus der Zeit das erste Mal das Wort «Dada», das er auch als Titel für eine geplante Zeitschrift vorschlug. Trotzdem bleibt unklar, wann und wer das Wort «Dada» tatsächlich gefunden hatte und worauf sein Ursprung zurückgeht. Bevor das Cabaret Voltaire zu seiner letzten bekannten Veranstaltung am 6. Juli 1916 die Türen öffnete, fand am 23. Juni 1916 eine Soiree statt, an der Hugo Ball erstmals seine drei Lautgedichte im kubistischen Kostüm als magischer Bischof präsentierte. Das Cabaret Voltaire war Treffpunkt und Versuchslabor neuer Ausdrucksformen, wie dem Laut- und Simultangedicht, intermedialen Aufführungen sowie neuen Bewegungsformen.

Nach der Schliessung des Cabaret Voltaire fand am 14. Juli 1916 der 1. Dada-Abend im Zunfthaus zur Waag statt und im Januar 1917 initiierte Han Corray in seiner Galerie an der Bahnhofstrasse im Sprünglihaus die Ausstellung «Modernste Malerei, N*plastik, Alte Kunst», die erstmals dadaistische Arbeiten und afrikanische Kunst gemeinsam präsentierte. Später übernahmen die Dadaist*innen die Räumlichkeiten und eröffneten am 29. März 1917 die Galerie Dada. Neben zwei Ausstellungen mit dem Titel «Sturm» im März und April 1917 sowie der Ausstellung «Graphik, Broderie, Relief» im Mai 1917 veranstalteten sie fünf Soireen in der Galerie Dada von den insgesamt acht Soireen, die ausserhalb des Cabaret Voltaire stattfanden und im Unterschied dazu mit Programmblatt, persönlichen Einladungen und Eintritten durchgeführt wurden. Trotzdem blieb der Charakter ihrer Soireen erhalten und es wurden Stücke teils erneut aufgeführt und weiterentwickelt. Zudem erhielt, neben den bereits entwickelten Maskentänzen, auch der abstrakte und expressionistische Tanz, in der Tradition von Rudolf von Laban, mehr Aufmerksamkeit.

Am 1. Juni 1917 mussten die Dadaist*innen die Galerie aufgrund vertraglicher Schwierigkeiten und finanzieller Engpässe sowie dem Zerwürfnis zwischen Ball und Tzara aufgeben. Nach der Schliessung kehrten Hennings und Ball ins Tessin zurück. Es fanden lediglich noch zwei weitere öffentliche Veranstaltungen in Zürich statt; am 23. Juli 1918 die 7. Dada-Soiree (Soiree Tristan Tzara) im Zunfthaus zur Meise und die letzte und 8. Dada-Soiree am 9. April 1919 im Saal zur Kaufleuten.

Dada global

Mit der Absicht, den Krieg und das nationale Streben zu bekämpfen sowie darin enthaltene Konzepte von Staatlichkeit und Hierarchie zu überwinden, strebten die Dadaist*innen transnationale Verbindungen an. Dada sollte zum verbindenden Prinzip avancieren und dabei selbst zugleich immer wieder neu gelesen und aufgeladen werden können. Mit dem Ziel Dada als Bewegung zu verbreiten, entwickelten die Dadaist*innen ein internationales Netzwerk, woraus rhizomartig neue Dada-Filialen mit eigener lokaler Verankerung entstanden. Grundlegend für die Verbreitung der Bewegung waren Briefwechsel, eine gezielte Medienarbeit und insbesondere auch Zeitschriften, welche die Dadaist*innen trotz der anfangs kriegsbedingt schwierigen Situation international vertrieben. Sie dienten als Plattform zur Bekanntmachung und Manifestierung ihrer Ansichten und Ausdrucksmittel.

Als Dada 1919 in Zürich verebbte, hielten Walter Serner und Christian Schad bis Mitte 1920 in Genf noch die Stellung, bevor sich Dada gänzlich ausserhalb der Schweiz und durch bereits geknüpften Kontakte weiterentwickelte. So zum Beispiel in Berlin, wo Raoul Hausmann, John Heartfield, Wieland Herzfelde, George Grosz, Hannah Höch und Johannes Baader 1918 den Dada Club Berlin gründeten. Dada gestaltete sich hier als politische Propaganda; mittels Magazinen, Flugblättern und Plakatgedichten reagierten die Dadaist*innen auf die Gesellschaft und das System, wobei sie auch die Fotomontage entwickelten. Höhepunkt in Berlin war die «Erste Internationale Dada Messe» am 14. Juli 1920, die später auch nach New York reisen sollte. Parallel zu Berlin formierte sich im Herbst 1919 mit Max Ernst, Johannes Theodor Baargeld und Hans Arp kurzzeitig ein Dada-Ableger in Köln und zur gleichen Zeit gründete Kurt Schwitters in Hannover seine eigene Bewegung Merz, nachdem ihm der Beitritt zum Dada Club Berlin verwehrt wurde. Schwitters führte nicht nur eine enge Freundschaft mit Hannah Höch, sondern ging 1923 mit Theo und Nelly van Doesburg auch auf Dada-Tournee nach Holland und mit Hausmann nach Prag, wo ebenfalls Dada-Filialen entstanden. 1920 traf Tzara auf Einladung von André Breton aus Zürich in Paris ein und fand eine literarische und künstlerische Szene vor, die durch Breton, Philippe Soupault, Louis Aragon, Céline Arnauld und Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes vorangetrieben wurde. Im Sinne von Dada fanden unzählige Veranstaltungen statt, die ebenso provokativ wie spektakulär waren. Durch stilistische Meinungsverschiedenheiten kam es am 6. Juli 1923 an der Soiree du Coeur à Barbe zu einem Eklat zwischen Tzara und Breton, was den Tod von Dada und die Geburt des Surrealismus initiierte. Während der gemeinsamen Zeit von Tzara und Janco in Paris, entfremdeten sich die beiden endgültig voneinander, woraufhin Janco zurück nach Bukarest ging. Dort gründete er das Kulturunternehmen Contimporanul und veranstaltete 1924 die «Erste Internationale Contimporanul-Kunstausstellung» an der viele Dadaist*innen vertreten waren. Parallel zu Jancos Rückkehr nach Bukarest trat Dada dank Walter Serner zunächst in Okayama, danach in Tokio erstmals in der Zeitschrift Dadaizmu sowie in den Poesiesammlungen von Shinkichi Takahashi auf. Zur gleichen Zeit suchte Tomoyoshi Murayama Kontakt zu Dada in Berlin und gründete im Anschluss seine Künstler*innengruppe Mavo. In New York war Dada bereits 1913 da, bevor Dada da war; so kamen Francis Picabia und Marcel Duchamp aus Paris angereist und bildeten zusammen mit Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Katherine S. Dreier, Man Ray, Beatrice Wood, Arthur Cravan, Louise und Walter Conrad Arensberg, Marius de Zayas, Alfred Stieglitz und anderen die künstlerischen Avantgarde in New York. Insbesondere mit der Entwicklung des Readymades durch Marcel Duchamp und Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven stellten sie bereits vor der Zürcher Bewegung wesentliche Fragen über die Bedeutung von Kunst. Trotz der Parallelen zu Zürich war Dada in New York flüchtiger und individualistischer, weshalb sie erst ab 1921 das Wort «Dada» für ihre Zwecke nutzten.

Als Vicente Huidobro 1916 von Chile nach Europa reiste, verbreitete er nicht nur sein Konzept Creacionismo, sondern wurde insbesondere in Paris Teil der Dada Bewegung und inspirierte in Madrid den Ultraismus. 1925 zurück in Chile schrieb er in Reaktion auf die Studentenbewegung insbesondere Artikel und Pamphlete. Ebenso wie Rafael Barradas, der in Barcelona den Begriff Vibrationismus prägte, war Jorge Luís Borges Teil der Ultraisten und trieb zurück in Argentinien seit 1921 die Verbreitung des Ultraísmo weiter voran. Auch Joaquín Torres-Garcia lebte in unterschiedlichen Städten in Europa sowie in New York. Er gründete seinen eigenen avantgardistischen Stil Universalismo Constructivo und widmete sich seit 1934 zurück in Uruguay ebenfalls der Verbreitung seiner Theorien. Oswald de Andrade war nicht nur wegweisend für den Modernismo in Brasilien, sondern schuf mit dem Manifesto Antropófago 1928 einen wesentlichen Beitrag zur Anthropophagie-Bewegung, die einen Gegenpol zur dominierenden europäischen Bewegung bildete. Andere Dada-Filialen und verwandte avantgardistische Bewegungen fanden sich in weiteren Städten in Deutschland und Spanien sowie in Italien, Österreich, Belgien, Polen, Russland, Kroatien und Slowenien wieder.

Trotz aktiver Selbsthistorisierung der Dadaist*innen seit Beginn ihrer Bewegung, wurde Dada zunächst und auch aufgrund des Zweiten Weltkriegs verschüttet. Erst ab den 1950er Jahren lebte Dada in neuen künstlerischen Bewegungen wie dem Lettrismus, Neo-Dada und Nadaísmo, der Situationistischen Internationale, der Beat-Generation

und Konzeptkunst sowie in Fluxus wieder auf und kann als wesentlichen Ausgangspunkt der heutigen Performance-Kunst bezeichnet werden.

Wiederbelebung des Cabaret Voltaire seit 2002

Nach der Schliessung des Cabaret Voltaire 1916 folgte eine lange Zeit diverser Zwischennutzungen der Räumlichkeiten. 2002 wurde das Cabaret Voltaire aus politischer und künstlerischer Überzeugung von einer Gruppe besetzt, wodurch dem Geburtsort von Dada neue Aufmerksamkeit geschenkt wurde und das Cabaret Voltaire 2004 unter dem Dach eines Trägervereins sowie mit der Direktion von Philip Meier «wiedereröffnete». 2006 wurde Adrian Notz Co-Direktor und von 2012–2019 alleiniger Direktor. Seit 2020 ist Salome Hohl künstlerische Leiterin und Direktorin des Cabaret Voltaire.

Englisch

Cabaret Voltaire is the birthplace of Dada and was opened in Zurich on the evening of February 5, 1916. This is where the history of the avant-garde art movement began, which not only shaped European modernism, but also art and society today. By the time Cabaret Voltaire opened – initially as the artists’ local «Voltaire» – Europe had already been through two years of war and was experiencing a major break in the sense of infinite upswing and growth brought about by colonial conquests and the Industrial Revolution. While the First World War was raging, many intellectuals, writers, anarchists, artists, and opposition members sought refuge in «neutral» Switzerland. There, in self-imposed exile, they directed their protests against the political climate and the ruling system and found places where they could exchange ideas and form alliances. Since living space in Zurich was scarce due to growing immigration, despite the economic boom in Switzerland, life took place mostly outside in coffee houses, vaudevilles, and cabarets, which were gaining popularity. At that time, the Niederdorf was the red-light district and the center of entertainment in Zurich. When Emmy Hennings and Hugo Ball arrived in Zurich in May 1915, they were initially active in various variety theaters, particularly Cabaret Hirschen, where Ball performed as a pianist and Hennings sang and danced as an experienced diseuse. Soon the theater maker Ball wanted to found his own cabaret, and he asked the landlord Jan Ephraim to let him the so-called «Holländerstübli» [Dutch wine tavern] in his dairy. The idea was to create an international cabaret, a place of artistic entertainment and intellectual exchange, whose stage was open to everyone. For the opening night, Hennings and Ball asked their friends both in Switzerland and abroad to contribute artistic works so that they could combine a small exhibition with a Kabarett [cabaret]. And so, on February 5, Sophie Taeuber and Hans Arp came along, painting the ceiling blue and the walls black, and, in addition to Arp’s own works, providing some works by Picasso, Arthur Segal, and Otto van Rees. Tristan Tzara, who recited Romanian verses, came together with Marcel Janco, whose archangel was hanged. Hennings sang some chansons on the stage, which was nailed together from planks, and a balalaika orchestra played Russian folk songs. The audience sat in the crowded room at tables with red tablecloths, separated from the stage by a green curtain. From the day of the opening until the closing of Cabaret Voltaire in July 1916, there were soirées every evening except Fridays. They consisted of musical, theatrical, and dance performances of all kinds, as well as recitations of texts and poems. Thematic evenings were also organized, including Russian, French, and Swiss soirées. Richard Huelsenbeck was not able to come to Zurich until February 26; he wanted to drum literature into the ground with his so-called «N* Drum». On April 18, 1916, Ball mentioned the word «Dada» for the first time in his diary Die Flucht aus der Zeit [flight from the time], a word he also suggested could be the title for a planned magazine. Nevertheless, it remains unclear who actually found the word «Dada» and when, and what its origin is. Before Cabaret Voltaire opened its doors for its last known event on July 6, 1916, a soirée was held on June 23, at which Hugo Ball presented his first three sound poems in cubist costume for the first time as a magical bishop. The Cabaret Voltaire was a meeting place and experimental laboratory for new forms of expression, such as sound poetry and simultaneous poetry, intermedia performances, and new forms of movement.

After Cabaret Voltaire was closed, the first Dada evening took place on July 14, 1916, in the Zunfthaus zur Waag, and in January 1917 Han Corray initiated the exhibition «Modernste Malerei, N*plastik, Alte Kunst»

[modern painting, n* sculpture, old art] in his gallery in the Sprünglihaus on Bahnhofstrasse, which for the first time presented Dadaist works and African art together. Later the Dadaists took over the premises and opened the Galerie Dada there on March 29, 1917. Besides two exhibitions named «Sturm» [storm] in March and April 1917 and the exhibition «Graphik, Broderie, Relief» [graphic, broderie, relief] in May 1917, they organized accompanying lectures and guided tours. Of the eight soirées that the Dadaists realized in Zurich, five took place at the Galerie Dada. In contrast to the time at Cabaret Voltaire, these were now held with program sheets, personal invitations, and admissions. Nevertheless, the character of their soirées was preserved, and some of the pieces were performed again and developed further. Furthermore, besides the mask dances that had already been developed, abstract and expressionistic dance, in the tradition of Rudolf von Laban, received greater attention. On June 1, 1917, the Dadaists had to give up the gallery due to contractual difficulties and financial bottlenecks as well as a dispute between Ball and Tzara. After the closure, Hennings and Ball returned to Ticino. Only two more public events were held in Zurich: the 7th Dada Soirée (Soirée Tristan Tzara) was held in the Zunfthaus zur Meise on July 23, 1918, and the last and 8th Dada Soirée on April 9, 1919, in the Saal zur Kaufleuten.

Dada Global

With the intention of fighting war and national aspirations and overcoming the concepts of statehood and hierarchy contained therein, the Dadaists sought transnational connections. Dada was to become a unifying principle, and at the same time it was to be read and recharged again and again. With the aim of spreading Dada as a movement, the Dadaists developed an international network, from which rhizome-like new Dada branches with their own local roots emerged. In addition to targeted media work, the distribution of the movement was based on magazines which the Dadaists distributed internationally despite the di cult situation caused by the war. The publications served as a platform through which to spread their views and means of expression.

When Dada ebbed away in Zurich in 1919, Walter Serner and Christian Schad maintained the position in Geneva until mid-1920s, before Dada continued to develop completely outside of Switzerland and through already established contacts: for example, in Berlin, where the Dada Club Berlin had been founded in 1918 with Raoul Hausmann, John Heartfeld, Wieland Herzfelde, George Grosz, Hannah Höch, and Johannes Baader. There, Dada turned out to be political propaganda; by means of magazines, leaflets, and poster poems, Dadaists reacted to society and the system, also developing photomontage. The highlight in Berlin was the «Erste Internationale Dada Messe» [first international Dada fair] on July 14, 1920, which was later to go to New York. In autumn 1919, parallel to Berlin, a Dada branch was formed in Cologne for a short time with Max Ernst, Johannes Theodor Baargeld, and Hans Arp; at the same time Kurt Schwitters founded his own movement, Merz, in Hanover, after he was refused entry to the Dada Club Berlin. Schwitters not only maintained a close friendship with Hannah Höch, but also went on a Dada tour to Holland with Theo and Nelly van Doesburg in 1923 and with Hausmann to Prague, where Dada branches were also established. In 1920 Tzara arrived in Paris at the invitation of André Breton from Zurich; there he found a literary and artistic scene that was driven by Breton, Philippe Soupault, Louis Aragon, Celine Arbaud, and Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes. In the spirit of Dada, countless events took place that were as provocative as they were spectacular. Stylistic differences of opinion led to an uproar between Tzara and Breton at the Soirée du Coeur à Barbe on July 6, 1923, which initiated the death of Dada and the birth of surrealism. After Tzara and Janco spent time together in Paris, the two became estranged for good, and Janco returned to Bucharest. There he founded the cultural enterprise Contimporanul and organized the «first international Contimporanul art exhibition» in 1924, where many Dadaists were represented. Parallel to Janco’s return to Bucharest, and thanks to Walter Serner, Dada first appeared in Okayama and then in Tokyo in the journal Dadaizmu and in the poetry collections of Shinkichi Takahashi. At the same time Tomoyoshi Murayama sought contact with Dada in Berlin and subsequently founded his artist group Mavo. In New York, the spirit of Dada was already there in 1913, before Dada had actually arrived; Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven and Marcel Duchamp, with their readymades, questioned the significance of art and found themselves together with other actors of the artistic avant-garde such as Louise and Walter Conrad Arensberg, Alfred Stieglitz, and the Parisian war refugees such as Francis Picabia, Arthur Cravan, Katherine S. Dreier, Edgar Varese, Henri-Pierre Roché, Suzanne Duchamp, Jean Crotti, and Marius de Zayas. Despite the parallels to Zurich, Dada was more ephemeral and individualistic in New York, which is why the word «Dada» wasn’t used for their purposes until 1921.

When Vicente Huidobro traveled from Chile to Europe in 1916, he not only spread his concept of Creacionismo, but became part of the Dada movement, especially in Paris, and inspired Ultraism in Madrid. Back in Chile in 1925, he wrote articles and pamphlets particularly in reaction to the student movement. Just like Rafael Barradas, who coined the term Vibrationism in Barcelona, Jorge Luís Borges was part of the Ultraists and, back in Argentina from 1921, continued to promote the spread of the movement. Joaquín Torres-Garcia also lived in various cities in Europe as well as in New York; he founded his own avant-garde style Universalismo Constructivo and, from 1934 on, back in Uruguay, also dedicated himself to the dissemination of his theories. Oswald de Andrade was not only a pioneer of Modernismo in Brazil, but with the Manifesto Antropófago of 1928 he made a signi cant contribution to the Antropofagia movement, which was a counterbalance to European dominance. Other Dada branches and related avant-garde movements were found in other cities in Germany and Spain, as well as in Italy, Austria, Belgium, Poland, Russia, Croatia, and Slovenia.

Despite the active self-historicization of the Dadaists since the beginning of their movement, Dada was buried initially and also because of the Second World War. It was not until the 1950s that Dada was revived in new artistic movements, such as Lettrism, Neo-Dada and Nadaísmo, the Situationist International, the Beat Generation, Conceptual Art, and Fluxus, and can be considered the starting point of today’s Performance Art.

Revival of the Cabaret Voltaire since 2002

After the closure of Cabaret Voltaire in 1916, the premises were used for a long time for various temporary purposes. In 2002, Cabaret Voltaire was occupied by a group out of political and artistic conviction. Their goal was to revive the birthplace of Dada. So in 2004 it was «reopened» under the roof of a supporting association and with the management of Philip Meier. In 2006 Adrian Notz became co-director and from 2012–2019 sole director. Since 2020 Salome Hohl is the artistic director and director of Cabaret Voltaire.

Aussenansicht des Cabaret Voltaire, 2021, Photo: Cabaret Voltaire, Aytac Pekdemir