From critical manifesto to transformative genderplay: feminist Futurist and Dadaist strategies countering the misogyny within the historical avant-gardes

An article by Sophie Doutreligne

Although misogyny was omnipresent within the greater part of the historical avant-gardes, the artistic responses to this attitude by female avant-garde artists were very diverse. I chose to focus in this article on the particular situation of female Futurist artists Valentine de Saint-Point, Mina Loy and Giannina Censi, and Dadaist artists Sophie Taeuber and Emmy Hennings. After outlining the complex and much-debated terminology of the ‘historical avant-gardes’, I will then zoom in on the particular contexts in which Futurism and Dadaism emerged. Subsequently, the problematic reception of these female pioneers of the historical avant-gardes will serve as the background in order to interpret my case studies’ artistic strategies of my case-studies of protesting the ongoing misogyny.

When speaking of the ‘historical avant-gardes’, a melting pot of different artistic movements roughly between 1905 and 1935 is intended (Bru 1). A term with an interesting etymology, the ‘avant-garde’ in ‘historical avant-garde’ initially was used within a military context, to describe a group of soldiers sent out to explore potentially hostile territory (215). In 1825, the French philosopher Claude Henri de Saint-Simon was the first to detach the term from its original reference to warfare, applying it within an artistic context (216). In his utopian plan for a socialist nation, he expected artists to lead the socio-economic revolution he envisaged by means of experimental, ‘avant-garde’ art. While de Saint-Simon roughly considered all avant-garde art experimental, the term gradually evolved to become something much more radical and greatly opposed to what was considered to be traditional art. Later, critics including Hans Magnus Enzensberger (1962) and Peter Bürger (1974) coined the term ‘historical avant-garde’ in order to avoid confusion with post-war movements (e.g., Neo-Dada) (218).

However, the ‘historical avant-garde’ was (and still is) subject to critical debate among scholars, more specifically when it comes to outlining the shared artistic project of the different movements that are considered part of this ‘historical avant-garde.’ Peter Bürger (author of the iconic Theorie der Avantgarde) concluded that the historical avant-gardes altogether aimed to unify art and life by attacking the concept of art as an institution. In doing so, they heavily contradicted the modernist project of creating an autonomous and self-reflexive art (Bürger 2010, 696). This statement was contested among (many) others by Susan Manning in her research on the revolutionary dances of Mary Wigman. Manning saw in the genre of the Ausdruckstanz (German Expressionist dance) not only a tendency towards uniting art and life, but also a drive to the creation of an autonomous form of art (a goal that was considered ‘modernist’ by Bürger). As such, Mannings questioned the strict applicability of Bürger’s definition of the ‘historical avant-garde’ to the field of dance and performance (Manning 7). Finally, while Bürger mainly focused on the overall project of unifying art and life, other scholars (e.g., Clement Greenberg) interpreted the avant-gardes in terms of their contradiction to mass consumption and mass production (Bru 220). I adopt the view that the term covers many difficulties, especially in the field of dance and performance (see also Manning). Rather than untangling this debate, I focus on two movements within the avant-garde period: Futurism and Dadaism, and the particular artistic strategies that female pioneers developed within these realms.

Futurism was founded by main representative Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. His controversial and energetic body of thought was internationally spread through the publication of his iconic The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (on the front page of the French newspaper Le Figaro in 1909) (Rainey 1). Originating in Italy, at a time marked by great changes caused by upcoming Modernity, Futurism aimed at installing a radical and new culture that incorporated the glorification of the machine, the beauty of warfare as “the only hygiene of the world” (Marinetti 1911, 84) and the language of speed. While Futurism initially started as a literary movement, it soon embraced a variety of artistic genres and media: visual arts, poetry, theatre, music, architecture, and even cooking. Central to the movement was the creation of sensory experiences that involved all of the senses of the participating spectator (Greene 21): “Painters have shown us the objects and the people placed before us. We shall put the spectator in the center of the picture” (Balla 1910, 65). The objective of merging art and life was best achieved through the organization of different Futurist Serate’s (evening performances). These evenings exploited the Futurist love of war, shock, violence and aggression in a programme that consisted of performances, concerts and exhibitions (Berghaus 90). In a later stage, Futurism became deeply involved with Fascism (Rainey 1).

While Futurism rooted in Italy and was very engaged in politics, Dadaism originated in neutral Zurich. Founded on the 5th of February 1916 by Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings (accompanied by Hans Arp, Richard Huelsenbeck, Marcel Janco and Tristan Tzara) (Amrein 7), Dadaism also aimed at unifying art and life (28). Still, the indirect confrontation with the horrors of World War I led to a disillusioned and dismissive stance towards war and violence: “While the cannon rumbled in the distance, we pasted, recited, versified, we sang with all our soul. We sought an elementary art, which, we thought, would save men from the curious madness of these times. We aspired to a new order which might restore the balance between heaven and hell” (Arp qtd. in Jones 67). The arrival of a great deal of immigrants of different backgrounds in Zurich granted Dadaism its international character and its multilingual and diverse cross-pollination of different styles and contents: Marinetti’s Futurist texts were published in Dada periodicals (Salaris 39), Expressionist dancers performed on the Dada stages, artists of the German Werkbund attended the Dada Soirées, etc. Finally, “Dadaism belonged to the stage” (Huelsenbeck qtd. in Amrein 10) as realized through the many Dadaist Soirées that brought together music, dance, poetry and the visual arts in a context that installed a renewed attention to the human body (11).

“I was also around”

The problematic reception of female pioneers of the historical avant-gardes

Art history at times creates the illusion that the historical avant-gardes consisted of a heroic group of white men bravely fighting bourgeois art standards (think of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Hugo Ball, Marcel Duchamp, etc.) (Jones 19). More often than not, equally engaged female artists such as Emmy Hennings who co-founded Dadaism with Hugo Ball in 1916, were reduced to passive ‘others,’ ‘wives of’, or trivial attendees.

However, a great number of female pioneers (e.g., Suzanne Perrottet, Nelly van Doesburg, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Suzanne Duchamp, Hannah Höch, Meret Oppenheim, Benedetta, Claude Cahun and many more) were heavily involved in the founding and the development of eminent artistic movements (Futurism, Dadaism, Surrealism, etc.) within the historical avant-gardes. Reducing the historical avant-garde to a ‘men-only club’ is not only a historical misconception, it also erases a vast amount of the diversity and complexity inherent in these movements. Rather problematically, it simply understates the importance of concepts such as gender and identity in the artistic work of both men and women going through great social, political and philosophical changes. Only in the eighties (Dech 1989), culminating in the nineties of the twentieth century, did historians start to rewrite avant-gardist art history from a feminist point of view, hence allowing avant-garde women to be recognized as active “innovators” rather than as passive “followers of male examples” (Deepwell 5). Valuable historical studies on Mina Loy and Elsa Von Freytag-Loringhoven, for example, and the more recent publications on ‘the gender of Modernity’ (Felski 1995, De Zegher 1996, Sawelson-Gorse 1998, etc.) were written. Nevertheless, these historical studies remained mainly biographical or descriptive studies. It is only now that art histories are uncovering the manifold artistic strategies of these female pioneers.

Before exploring the artistic strategies of some of these female pioneers, I ask myself the following questions: Why is it that these female pioneers of the historical avant-gardes were underexposed in art history for so long? How do we understand the practice of silencing their artistic contributions and at times even denying their existence outright?

First, a number of culturally defined circumstances and prejudices contributed to the marginalization of the female avant-garde artist in society. As most of the avant-garde movements originated in cities and at venues where women were often not welcome if unaccompanied by men, they were often prevented from actively participating (Bru 107). Moreover, their position as a female ‘other’ directly affected their financial status, which often forced them to look for alternative sources of income as well as encouraging them to operate anonymously within the avant-gardes. Dadaist Emmy Hennings, for example, had to turn to prostitution to compensate for her unpaid artistic activities: “the poor girl gets too little sleep. Everybody wants to sleep with her, and since she is so accommodating, she never gets any rest. Until 3 a.m.; she has to be at Kathi’s place, where she is taken horrible advantage of, and by 9 a.m. she is already at art class” (Erich Mühsam qtd. in Hemus 2009, 21). Emmy Henning’s Dadaist colleague and friend, Sophie Taeuber, had no other choice than to sign the Dada manifesto with the pseudonym G. Thauber, while also dancing the Dada stages anonymously (wearing concealing masks and costumes) out of fear of losing her income as an art teacher (Bolliger 33). Futurist Mina Loy similarly employed a certain “pseudonymania” (Conover xviii) and even enjoyed the advantages of the appealing and mysterious aura it bestowed on her (Lusty 245). In the same tradition, fellow Futurist Valentine de Saint-Point, officially named Valentine de Anne-Jeanne-Valentine-Marianne Desglans de Cessiat-Vercell Saint Point, amused herself by combining and re-combining parts of her name in a confusing way while boasting of various extraordinary blood-relations (Satin 2).

Second, the commonplace derogatory and belittling attitude of male colleagues condemned female avant-garde artists to being outsiders, “alien, as woman and as human being” (said Hans Richter about Emmy Hennings qtd. in Hemus 2009, 19-20). The many statements of Dada artists bear witness to this phenomenon, including Suzanne Perrottet’s lamentation “I was also around” (Kamenisch 10), Sophie Taeuber’s request “Why can’t I also be a Dadaist” (Boesch 109) and Hania Routchine’s “I hope you will do me the honour of listening” (Ingram 18). All too often it seemed as if men were the ones actually creating art whereas female artists, at best, passed as “gifted amateurs” (Dadaist Hannah Höch qtd. in Boesch 2). Furthermore, as soon as they succeeded “too well” in terms of “male standards,” they were blamed for “denying their female nature” (Orenstein 33). In the case of dance and performance specifically, their artistic qualities were played down in favour of the sensational effect they were expected to produce (Hemus 2009, 28). Some fellow Dadaists saw nothing more than a “pleasurable visual spectacle for the men in the audience” in the Dada dancers (Hemus 2007, 97).

This practice of gazing resembles what feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey called ‘the male gaze’. In her much-discussed essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative cinema”, Mulvey turns to psychoanalysis to analyse the overall present ‘male gaze’ that constituted classic Hollywood cinema. This ‘male gaze’ installed a way of looking at a woman (as portrayed on the screen) that reduced her to a passive object of pleasure, one that the spectator could only desire and never identify with (Mulvey 63). I will not go into too much detail with regard to the debate around Mulvey’s theory, but it is clear that in reading the many romanticizing reviews of female Dada performances, in which the appeal of the performers’ bodies overshadowed the technicality of their movements, this concept of the ‘male gaze’ is also at stake: “her dance patterns are full of romantic desire, grotesque and enraptured,” Hugo Ball observed (Hemus 2007, 98). A description of Belgian Surrealist Jane Graverol’s paintings as products of “a very feminine extravagance,” further illustrates the objectifying ‘male gaze’ in describing women’s art (René de Solier qtd. in Orenstein 49). Not only were these pioneers as such romanticized, they were also often overtly described as sexual bait for a mainly male audience who responded to their alluring sexual presence (Hemus 2009, 22). Dadaist Emmy Hennings, for example, was considered “the cosmopolitan mixture of god and brothel” (Tristan Tzara qtd. in Hemus 2009, 28) rather than being praised for her virtuous capacities as a versatile singer, writer and actress (19).

Both the difficult position of avant-garde women in society, as well as the derogatory attitude of colleagues and critics, contributed to the fact that women artists were never fully accepted as autonomous creators. Rather, they were considered to be passive muses for the creative potential of their male colleagues. In addition, the rigid classification and prioritization of certain media and materials through art history contributed to the unjust exclusion of many avant-garde women (Buckley 3). “Feminine” media (embroidery, fashion, dance) and materials (wood, textile, the body) were generally considered inferior in the established art world and were only judged according to their utility, whereas men’s art (written texts, sculpture, paintings) was unquestioningly accepted into the market economy (5). As an example, art educator Hugo Weber in his Catalogue Raisonné (1948), neglected a great deal of Sophie Taeuber’s embroidery, tapestry and jewellery in favor of her work as a visual artist (Bargues 103) because of these pejorative connotations. Still, as Taeuber tried to prove and as her husband and colleague Jean Arp noted: “Art can just as easily express itself in wool, paper, ivory, ceramics, or glass as in painting, stone, wood or clay” (103-104).

In the case of dance and performance, not only this inferior status, but also the limited sustainability of the media led to a “disciplinary blindness towards its (dance’s) cultural and historical significance” (Andrew 17). Moreover, the short-lived and volatile status of these art forms, leaving us with nothing more than a few photographs and testimonies, makes it particularly challenging to bring to life female avant-garde performance. This has consequences right up to the present day. In visual culture studies, for example, Hal Foster (in his article “Dada Mime” (2003) reduced the iconic image of Sophie Taeuber dancing at the opening of Cabaret Voltaire / Galerie Dada (1916/17) to a mere illustration of the mask she was wearing, “leaving her a stand-in for any masked Dadaist” (Andrew 17, see also Foster 170). By separating the mask from the dancing body moving with it, Taeuber’s bodily presence as a dancer is painfully denied. Not only did this lead to a misconception of Taeuber’s iconic dance performance(s), it also undermined the enchanting influence of masks upon the moving Dada body (see Doutreligne and Stalpaert 2019) informed by the different brochures announcing Dada events from 1916 on, dancing and moving with masks played an important role in the arrangement of every single Soirée. Moreover, the masks, “reminiscent of the Japanese or ancient Greek theatre, yet […] wholly modern” had a compelling and dialogical effect (Ball 64) upon the performing body. In Ball’s celebrated Dada diary, this particular effect is described extensively:

We were all there when Janco arrived with his masks, and everyone immediately put one on. Then something strange happened. Not only did the mask immediately call for a costume; it also demanded a quite definite, passionate gesture, bordering on madness. Although we could not have imagined it five minutes earlier, we were walking around with the most bizarre movements, festooned and draped with impossible objects, each one of us trying to outdo the other in inventiveness. The motive power of these masks was irresistibly conveyed to us. All at once we realized the significance of such a mask for mime and for the theatre. The masks simply demanded that their wearers start to move in a tragic-absurd dance. (64)

Both attitudes of contemporaries (resembling Mulvey’s descriptions of the ‘male gaze’) and subsequent patriarchal stance of traditional art history, rendered female avant-garde artists silent and invisible. However, it was precisely through their specific interventions through well-chosen media as well as materials that these artists strongly criticized and deconstructed reigning concepts of logic, language, and gender. Starting from their marginalized position (both as women and as a members of the avant-gardes) the female Futurists and Dadaists that I will discuss next reinvented themselves while radically claiming their right to exist in two crucial ways. First of all, by critically addressing the misogynist cult of Futurism in its own familiar tongue: constructing a verbal alternative, a ‘female gaze’, in the form of a “feminist” manifesto. Second, by literally embodying the bankruptcy of the traditional concept of binary gender that was complicit in the conviction of my case-studies (both the Futurists as well as the Dadaists) as ‘outcasts.’

Establishing a female gaze: “Feminist” Futurist avant-garde manifestos

The manifesto was a popular and efficient artistic genre as well as a means of communication to launch and spread the intentions of different avant-garde movements internationally. Quite symbolically, it functioned as a “flag to alert to others that something new had started,” that a “virgin territory in the arts had been claimed” (Bru 9). When it comes to Futurism, the manifesto listed bold statements in which traditional art conventions were destroyed: “We intend to destroy museums, libraries, academies of every sort, and to fight against moralism, feminism, and every utilitarian or opportunistic cowardice” (Marinetti 1909, 51). Moreover, these manifestos were written in a direct and aggressive tone, mining an explicit and often warlike vocabulary, while engaging a collective ‘us’ against inferior ‘other(s).’

However textual (literally bound to the page) this genre might initially seem, there was more to it than meets the eye. The manifesto was meant to act not only as a textual, but also, and even more importantly, as a performative gesture. A theatrical action that was challenging the limits of language itself, demanding an engagement of all of our senses. Furthermore, the Futurist manifesto referred frequently to womanhood in terms of submission and domination: “Yes, our nerves demand war and disdain women, because we fear that supplicating arms will entangle our knees in the morning of departure!... What do they want – women, sedentary people, invalids, the sick, and all counsellors of prudence?” (Marinetti 1909, 54), “we male Futurists have felt ourselves abruptly detached from women, who have suddenly become too earthly or, better yet, have become a mere symbol of the earth that we ought to abandon” (Marinetti 1915, 89). And even: “the heat of a piece of wood or iron is in fact more passionate, for us, than the laughter or tears of a woman” (Marinetti 1912, 122).

Several female Futurist artists engaged with the particularly masculine format of the manifesto in order to deal with the narrow-minded and stereotypical imagery of their time. Despite the fact that the feminist ideal of the “New Woman” (together with the important struggles of the Suffragettes for example) emerged and gained importance throughout Europe and America at the beginning of the twentieth century (“And out of houses that were once reigned over by little doll-women have sprung new women (their hair drawn up at the nape of their necks and if necessary wearing trousers instead of skirts), women workers, women tram drivers, women street sweepers, women nurses (…))” (Futurluce 251), this radical shift in traditional gender roles was mostly met with fear and scepticism.

As such, female Futurists saw in the manifesto a medium through which they could address their male colleagues in the disguise of a familiar tongue, while taking the opportunity to critically question and denounce their subordinate position. The manifesto thus functioned as a literary safe space in which suggestions for improving the social and artistic status of women could be expressed.

Without wanting to confine the movement of Futurism solely to its openly misogynist character (a concern rightfully pointed out by Ré Lucia in her article about Futurist artist Mina Loy), it is essential here to take into consideration how Futurist women reacted to this derogatory attitude and contesting of their radical statements on gender constructions in society. Futurist writer, poet and dancer Valentine de Saint-Point was the first to call attention to her marginalized position. Through her lectures she investigated and exposed the gendered inequalities through history. Her reading on the Theatre of Women for example, outlined the problematic depiction of women by playwrights throughout history leaving women and their sexualities unrepresented (Berghaus 28).

Furthermore, her militant feminist Manifesto of the Futurist Woman (1912) was a direct attack on Marinetti’s misogynist statement at the beginning of his manifesto: “we will glorify war – the world’s only hygiene – militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and contempt for woman” (Marinetti 1909, 51). In her powerful reaction (first recited 3 June 1912 in Galerie Giroux in Brussels and later on 27 June in Salle Gaveau in Paris (Berghaus 29)), de Saint-Point not only claimed equality between men and women (“both merit the same disdain”) but also called for an incorporation of both femininity and masculinity in every human being: “It’s absurd to divide humanity into women and men; it is composed only of femininity and masculinity” (de Saint-Point 109).

In leaving behind traditional notions of men being ‘masculine’ and women being ‘feminine,’ de Saint-Point effectively succeeded in liberating biological sex from gender constructions. Moreover, her progressive text introduced a radically different version of the “new man” envisioned by the Futurists: an androgynous and sexually liberated human being. As an alternative to the passive and exclusively ‘feminine’ images of women (for example the traditional image of woman as a mother), de Saint-Point introduced her idea of “women warriors” (Satin 4). Inspired by the “Amazons”, the “Joan of Arcs” and the “Cleopatras”, these androgynous warriors could even “fight more ferociously than men” (de Saint-Point 111). Although her stance on the incompatibility of the roles of lover and mother liberated women in an ambiguous way, at the same time it “condemned them to nurture and support male heroes by engendering or desiring them without sentimentality or passionate involvement” (Franko 22).

Another critical voice not afraid to speak up was Futurist writer, poet, and painter Mina Loy. Although curiously ignored by the majority of poets and critics of her own generation (Conover xxvii), as well as initially overlooked by historians of the avant-garde (xxxiv), Loy can be considered a pioneer of free verse (xxvii). Her poetry stigmatized Futurist misogyny and mocked Marinetti’s macho cult, “making in fact a kind of poetic reputation for herself out of repeated (and well-deserved) Marinetti-bashings” (Re 2009, 811). Inspired by the energy, movement, and wittiness of Futurism as a movement while at the same time multiplying the ‘I’ in her poetry, she soon learned to turn the Futurists’ own weapons against them (806).

Her visionary literary critique on the misogynist nature of Futurism will be discussed through Aphorisms on Futurism (1914) and Feminist Manifesto (1914). Aphorisms on Futurism (1914) was first published in Alfred Stieglitz’s Camera Work (803) and ambiguously combined an aggressive and emotionless style with a more personal, almost intimate subject matter. This can be seen in the way that while all of the aphorisms start in capital letters, and many of them seem to incite commands: “UNSCREW your capability of absorption and grasp the elements of Life – Whole” (Loy 274), Loy nonetheless managed to install a sensitive undertone to the seemingly rational and emotionless cover of style and typography. More specifically, as well as some general aphorisms such as: “MAN is a slave only to his own mental lethargy,” she included statements that seemed to aim for the more intimate project of self-fulfilment: “CEASE to build up your personality with the ejections of irrelevant minds” and “MAKING place for whatever you are brave enough, beautiful enough to draw out of the realized self” (ibid). That her controversial composition of content and style was radical, even for contemporaries, was informed by the unsettled reaction of Alfred Kreymborg to her work: “if she could dress like a lady, why couldn’t she write like one?” (Lusty 249). Aphorisms on Futurism enabled Loy to break free from all restrictions and expectations, both as a woman and as a writer (Pozorski 43).

Further, her Feminist Manifesto (written in 1914 but only published posthumously) forcefully accused socio-cultural institutions of their inadequacy in enabling women to express their own individuality and subjectivity (Lusty 252). Less rhythmical in composition and typography than Aphorisms on Futurism, the manifesto introduced the literary genre of the free verse (Re 2009, 811) and combined it with a content that was even more radical. Unlike Valentine de Saint Point, Loy problematically forced the solution of overcoming gendered inequities upon the female body itself. In proposing an “unconditional surgical destruction of virginity throughout the female population at puberty” (Loy 270), Loy hoped that manipulating – thus controlling – the female body would allow the construction of a female subjectivity (Walter 667). Even if it was felt this feminist goal could justify the means, it remains difficult – impossible even – to accept that the social construct of gender can only be changed by violating the female sex.

Her claim that women’s path to sexual autonomy can only be realized by “demolishing the division of women into two classes: the mistress and the mother. Every well-balanced and developed woman knows that no such division exists, that Nature has endowed the Complete Woman with a faculty for expressing herself through all her functions” (Loy 269-270), led some critics into reading her manifesto as a counterbalance to that of de Saint Point (Re 2009, 811). Still, “her allusion to parasitism and marriage as a kind of glorified prostitution was entirely in tune with Futurist vocabulary.” What was new was “her proud affirmation of female sexuality and maternity” (813). Her most revolutionary thoughts were “not in the transcendence of sexuality through mechanized man, but in the transformation of sexual codes: ending the false opposition of the ‘feminine’ body versus the ‘masculine’ mind” (ibid).

In comparing the feminist manifestos of Loy and de Saint-Point, the quest for equality between the sexes is realized in two radically different ways. De Saint-Point detaches biological sex from gender, claiming that both men and women must incorporate both masculinity as femininity, whereas Loy refuses to accept biological difference and believes in the outright manipulation of the female body. In this, it is important to state what kind of feminism each of these artists supported. First of all, both of them directly attacked feminism as a movement. De Saint-Point stated that “feminism is a political error,” (de Saint-Point 111) while Loy claimed that “The Feminist Movement as instituted at present is INADEQUATE” (Loy 269). Still, when analysing the content of their manifestos, their attitude is deeply feminist. The exception to this is Loy’s problematic proposal of “a surgical destruction of virginity” and her ideas on constructing a master race in which women were seen as the patriotic “reproducers of the nation” (Sica 349).

Transformative genderplay

Another artistic strategy dealing with the marginalization of the female ‘other’ was the playful performance of gender confusion. Already in Romanticism, an explicit tendency towards a so-called “androgyne imagination” (Rado 1) had emerged. Male writers had looked for, and experimented with, their own “feminine” qualities, intuitions, and sensitivities. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the feminist ideal of ‘New Woman’ further challenged rigid gender identities based on biological grounds alone (12). As most men were called to the front to serve in the war, women were now fulfilling traditionally assigned “masculine” roles, working as factory workers, drivers, railway guards, etc. This eventually also led to new, empowering, and androgynous notions of identity, followed by customized female fashion. ‘New woman,’ as presented on billboards, in literature, fashion, and the visual arts, thus communicated a crisis in the concept of the binary opposition of male and female, while on the other hand articulating dreams, desires, and possible futures of emancipation and empowerment.

The idea of ‘New woman’ fully infiltrated the historical avant-gardes (see Virgina Woolf’s novel Orlando, Futurluce’s (Elda Norchi’s pseudonym (Sica 154)) descriptions of new women with “drawn up hair” and “trousers instead of skirts,” the appearance of the “femme homme” in Dadaism, etc.). While we saw Futurist artists turning to the format of the “feminist” manifesto, we will now discuss how female Futurists as well as Dadaists turned to their own bodies to incorporate their revolutionary ideas about gender. As an archive of socio-cultural experiences, the female body absorbs the masculine expectations of it, while at the same time radically resisting the ongoing objectification of the male gaze. As such, the artists that will be discussed, resubmit themselves in patriarchal discourse, making visible what was supposed to remain invisible. A strategy that mimetically reproduces existing social gender codes, while also “playfully crossing” (Irigaray 76) the traditional gender boundaries, thereby exposing their problematic and outdated nature (119).

This strategy of genderplay will first be investigated within the movement of Futurism, and more specifically within the field of dance. Despite the fact that Futurism as a movement welcomed a very broad range of artistic disciplines, ceramics, visual arts, sculpture, music (noise art), etc., it never really managed to establish a solid base in order to develop Futurist dance as a full-fledged practice in the same way as music, the visual arts and theatre (Veroli 227). A series of questions comes to the fore: was there a lack of interest in the field of dance? Were there simply no artists wanting to translate or even reinvent Marinetti’s manifestos on dance? What influence did Marinetti’s “contempt for women” (Marinetti 1909, 51) have within this field? While we can only guess at the exact reasons for the Futurist under-exploration of dance, we do know for certain that there were two exceptions to this rule: Valentine de Saint-Point (already discussed through her meaningful manifestos) and Futurist dancer Giannini Censi (Veroli 227).

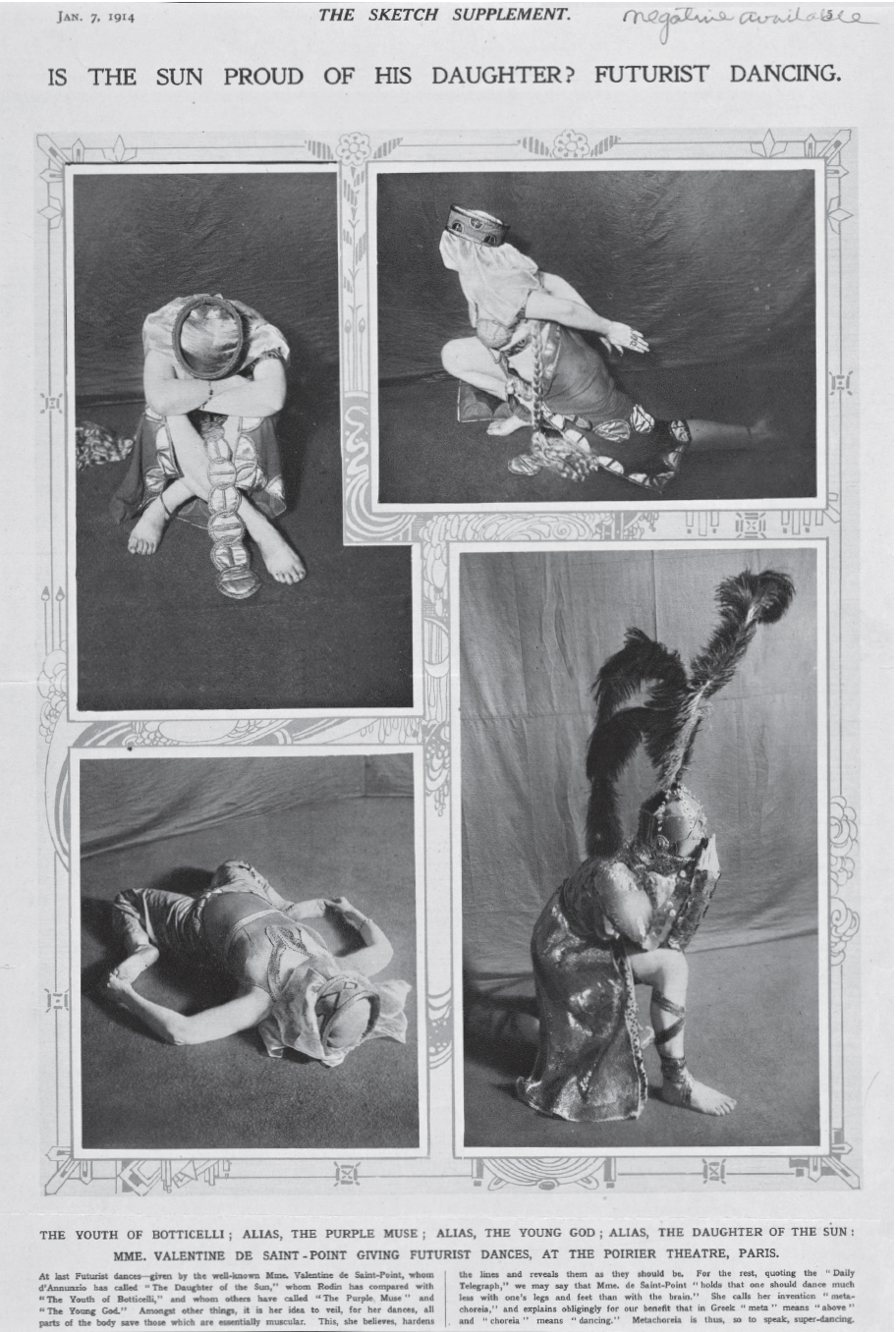

A year after having written her progressive feminist manifesto, de Saint-Point performed her Métachories for the first time at the Comédie des Champs Elysées (Paris) (Berghaus 30). Only a handful of pictures remain and inform us about the different outfits de Saint-Point wore during these performances. The art historian Günter Berghaus has divided the costumes stylistically in three categories: “Greek modelled drapery in bright colours, oriental clothes with rich textures and martial looking medieval outfits” (31). It is striking that in all of her costumes her face is covered with fabric, leaving no trace of facial expressivity or a possibility of identification. The only bare skin that can be perceived is through the occasional exposure of an arm, foot and knee. Her dances, introduced by an explanatory text and guided through recited poems written by de Saint-Point, consisted of four sections: Poèmes d’amour, Poèmes d’atmosphère, Poèmes pantheistes and Poèmes de guerre (ibid).

“Mme. Valentine de Saint-Point giving futurist dances at the Poirier Theatre, Paris,” (The Sketch Supplement, January 7, 1914, Image courtesy of the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts)

De Saint-Point’s critical stance towards traditional gender constructions can be illustrated in three examples. First, her quest for the necessary incorporation of both femininity and masculinity in every human being is materialized through her costumes. Her outfit in military armour reflects her ideal of “woman warrior”, as her veiled face not only deprived her of individual expression, it also concealed her overtly feminine features. A practice that was equally employed by Expressionist dancer Mary Wigman, who also blurred her female contours with costumes that were masking her body. In her dances, Wigman was never a gendered persona, but rather a dynamic configuration of energy in space (Manning 41). This was informed by testimonies, stating that “some have characterized Wigman’s art as masculine. ‘Impersonal’ is more apt” (67).

Second, the relation of her moving body with the music of Satie and Debussy echoed her quest of equality between man and woman, mind and body. De Saint-Point criticized the fact that classical dance often perceived music as male and dominant, while dance was interpreted as female and submissive. She radically challenged this relation in which dance was reduced to “an accessory to music” (de Saint-Point qtd. in Franko 22) by claiming that all the arts had to be valued equally (Berghaus 35): “my dream is of a dance which ranks equal with all other arts. It is not inferior to any of them, particularly not to music, to which, wrongly, it is currently enslaved” (de Saint-Point qtd in Berghaus 35). As such, her dances never relied on music, but instead they articulated ideas of their own (38). In the same way as dance had to be liberated from its dependency on music, women had to be freed from their submissive position towards men (Franko 22): “She will be, in short, a free and conscious woman and still most feminine. She is an expression of womanhood that is presently becoming more and more visible in society” (de Saint-Point qtd. in Berghaus 39). Finally, the specific movements of de Saint-Point on stage, alternating between sharp, precise, and geometrical movements on the one hand, with soft, smooth, and flowing gestures on the other (36), similarly revaluated the equality of mind and body.

In her Métachories, de Saint-Point performed a hybrid gender identity that was independent of biological limitations. Not only did she articulate her ideas on gender, even more, she embodied them with the purpose of becoming them corporeally. In doing so, her ‘ideistic dance’ (Franko 24) incorporated the forces of both mind and body: “instead of expressing through dance feelings or psychology, I seek to express an idea, the spirit which animates my poems” (Berghaus 35). By unsettling traditional gender connotations (both the connection of biological sex to gender as well as the stereotypical perception of mind as male and body as female), de Saint-Point powerfully claimed the stage in order to introduce her own feminist agenda: the ideal of “Warrior woman” of which she herself was the prototype. Further, through her Métachories she transformed the vulnerability of her own body into a Futurist ideal: an anti-body of “pure thought without sentimentality or sexual excitement” (Marinetti in Franko 22). Still, this anti-body didn’t lead to her own disappearance. Unfortunately, her ground-breaking ideas on gender and sexual liberation, as well as her innovations in the field of dance, never gave her the recognition she deserved among (dance) historians (Berghaus 40). This could partially be the result of Marinetti’s severe critique of her Métachories, and more specifically of the “passéist poetry” that was recited during these performances:

Unfortunately, it is passéist poetry that navigates within the old Greek and Medieval sensibility: abstractions danced but static, arid, cold, and emotionless. Why deprive oneself of the vivifying element of imitation? Why put on a Merovingian helmet and veil one’s eyes? The sensibility of these dances turns out to be elementary limited monotonous and tediously wrapped up in an outdated atmosphere of fearful myths that today no longer mean a thing. A frigid geometry of poses which have nothing to do with the great simultaneous dynamic sensibility of modern life. (Marinetti 1917, 236)

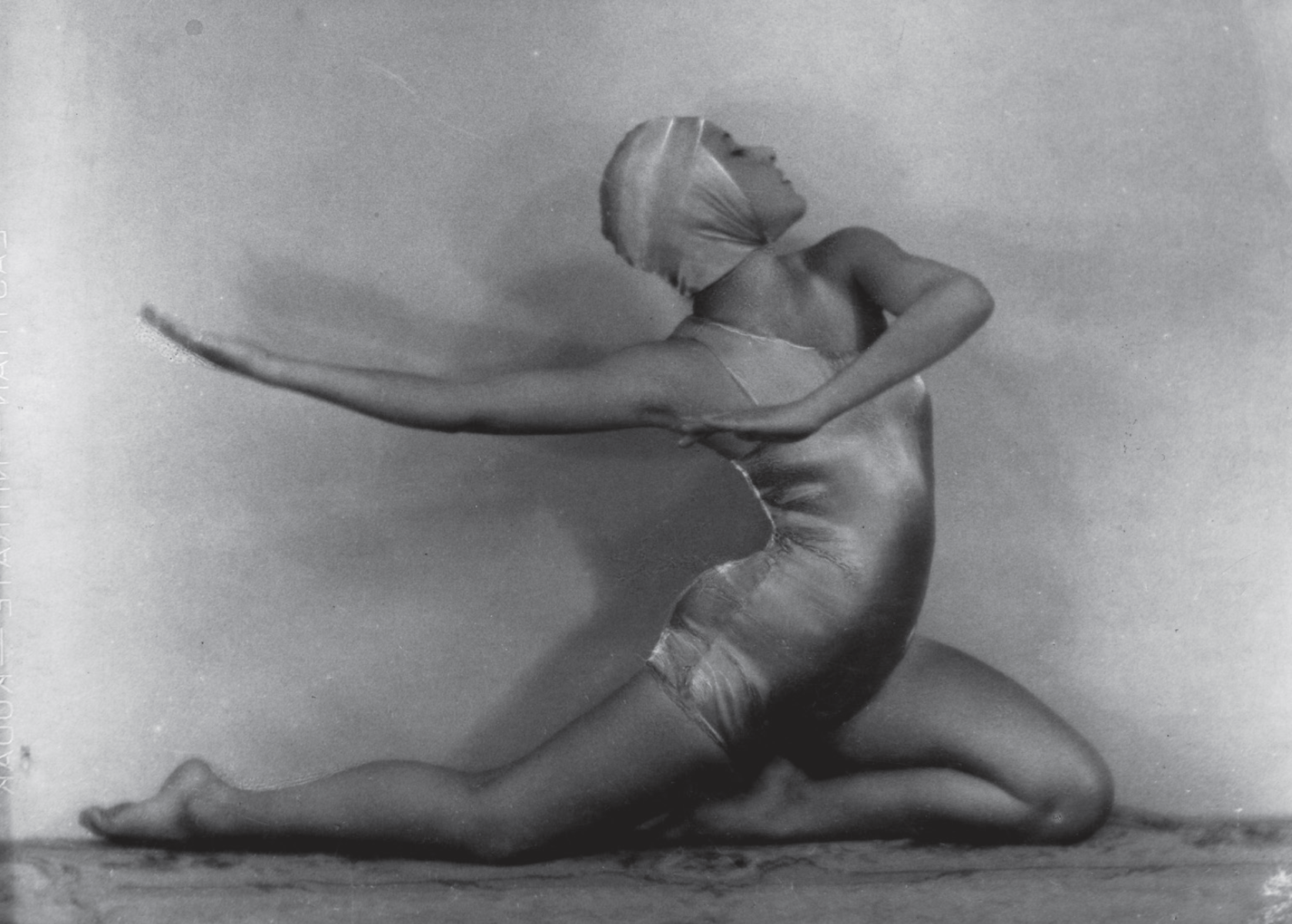

Finally, Futurist dancer and choreographer Giannina Censi is also known to have performed Futurist dances. In her Aerodanzes of 1930, Censi corporeally investigated the mechanical movements of an airplane (Klöck 397). Her costume, a shiny satin bodysuit designed by fellow Futurist Enrico Prampolini (Veroli 229), was filled with tubes and metal wires just before the performance. As such, her costume became an obstacle (Veroli 229), an essential antagonist in her performance that was therefore also no longer a monologue. Her performance, in which she embodied the fusion of woman with machine, blurred binary oppositions of woman / machine, nature / culture and body / mind. Moreover, it allowed her to exist within (speaking in a Futurist tongue) as well as to escape from the dominant Fascist ideal of women as reproductive machines serving no other goal than to produce soldiers for the Fascist programme (Klöck 407).

Aerodanze: partenza di aeroplano (departure of the airplane) (T. Santa Croce, Milano, 1931) (Reproduced with permission of Mart Archivio del ‘900 di Rovereto (Italy))

This tendency of cross-gendering the female body on stage was also at stake in Zurich Dada. In what follows, the performative practice and the relation to gender in the work of Sophie Taeuber and Emmy Hennings will be investigated. Sophie Taeuber was an interdisciplinary artist, who started her education at the famous Debschitz Schule (a school specialized in the applied arts) in Munich in 1910 (Mair 36). Passionate about dance, she subsequently applied for the Rudolf von Laban School in Zurich (54). She became a teacher in textile art at Zurich University of the arts, a member of the Werkbund (a German variant of the Arts and Crafts movement) (Bargues 103), and above all, a versatile artist who worked in a wide range of both art forms (sculpture, drawing, dance, painting, jewellery, etc.) and materials (wool, wood, paint, her own body). Her Dada friend and colleague Emmy Hennings, born Emma Marie Cordsen, started her career as a vaudeville artist, performing internationally between 1912 and 1915. She was a writer, a diseuse (a professional reciter), and a singer (Baumberger and Behrman 21). She founded Cabaret Voltaire in 1916 with Hugo Ball where she danced, acted and recited poems (Baumberger 35). Both Taeuber and Hennings are known to have danced at the Dada Soirées between 1916 and 1919.

As was the case in Futurism, the Dadaist relation to feminism and feminist ideas was not unequivocal either. Although not all male Dadaists were women-unfriendly, neither were all female Dadaists automatically feminists, “for women, who played an ancillary role at best within these movements … making a career for themselves often proved hard enough” (Bru 131). Hugo Ball wrote a letter to Emmy Hennings in 1916 in which he blames his Dada colleague for not taking Emmy seriously: “Hardekopf has treated you as a child […] thereby he had weakened your influence” (Swiss Literary Archive Bern, E-01-A-02-a). Raoul Hausmann’s genderless dances (Bargues 105) and the belief in matriarchy (Bru 132) also need to be nuanced in this way. What is essential to point out here, is that the risks in performing their progressive gendered dances simply were much higher for women than for their male colleagues who applied genderplay merely as a means to destroy the social nucleus of bourgeois culture tied to gender (Bru 132) (see the work of Duchamp, Man Ray, Hausmann and others). These female performers not only questioned rigid gender conventions, they also sought to insist on their right to exist within the art world.

The case of Sophie Taeuber’s Dada performances is unique because the picture preserved of her in Dadaist costume is one of the only remaining visual references to Dada performance. This exceptional photograph, taken either in 1916 in Cabaret Voltaire or in 1917 in Galerie Dada, is extremely instructive as to the meaning and the style of the Dada costume (see Doutreligne and Stalpaert 2019).

Sophie Taeuber at Galerie Dada 1916/17 (photographer unknown, 1916/17) (Stiftung Hans Arp und Sophie Taeuber-Arp e.V. Rolandswerth)

On the photo, we observe Taeuber wearing a long, straight, white dress and a frightening rectangular mask with a giant open mouth and dangerous-looking half open eyes (Doutreligne and Stalpaert 533). The mask (either made by Jean Arp or Marcel Janco), decorated in a Cubist fashion, ended in four sharp edges at the top, resembling the abstract idea of hair or alternatively a crown. The sharp edges, as well as her mechanical fingers along with parts of her dress, reflect the bundle of light that was directed at the upper body, leaving her legs and feet invisible and in the dark. Furthermore, the cardboard tubes that enclosed her arms resembled the ones that Ball wore during his performances as the Magic Bishop. They were so tight that it was impossible for her to bend her arms. Her dress was decorated with geometrical symbols and loose, hanging, shiny ribbons. Her body leaned to the back dramatically while her hands were crossed and raised, as if to protect her mask from the light bundle directed towards her. This picture gives us a unique insight into the theatrical language of Dada through mask and costume, yet however informative this picture is, it is important to keep in mind that it was not taken during, but rather before or after, the performance. As such, it functioned as a performance in its own right: a theatrical composition outlined in time and space, captured in one static picture.

Apart from the visual information we can glean from the photograph, historical sources inform us that Taeuber was in fact moving to recited sound poems by Hugo Ball (Damman 352). These poems, so typical of Dada in the way that ‘words-in-freedom’ were of Futurism, consisted of sounds and verbal particles that were completely dissociated from the logical structure of language. Language as they knew it was entirely discredited because it was the main vehicle employed to advertise and justify war (Demos 149) and therefore a new language needed to be invented: “Why can’t a tree be called Pluplusch, and Pluplubasch when it has been raining?” (Typescript of the manifesto presented on July 14, 1916 at the Zunfthaus zur Waag, second page, Estate Hugo Ball / Emmy Hennings, Swiss Literary Archive, Bern). Reports by contemporaries also inform us that there was a reciprocal relation between the dancing body and Dadaist sound poems. According to Ball, sound poems incited particular movements in the performing body:

The nervous system exhausts all the vibrations of the sound, and perhaps all the hidden emotion of the gong beater too, and turns them into an image. Here, in this special case, a poetic sequence of sounds was enough to make each of the individual word particles produce the strangest visible effect on the hundred-jointed body of the dancer. From a “Gesang der Flugfische und Seepferdchen” there came a dance full of flashes and edges, full of dazzling light and penetrating intensity. (Ball 102)

The individual sound and word particles of the recited sound poems were corporeally translated into (the movements of) Taeuber’s “hundred-jointed body” (ibid). In dancing to the verbal stuttering of the sound poems, Taeuber’s body became the stuttering itself (Doutreligne and Stalpaert 541): moving with a “jerky syncopated expressing” (Janco qtd. in Damman 360) while breaking into “a hundred, precise, angular, and sharp movements” (Ball xxxii). As such, Taeuber’s polyrhythmic (De Weerdt and Thurner 116) dance resembled the polyphonic improvisation characteristic of the musical genre of jazz (Marcel Janco in Damman 361). Her nervous performance described by Tristan Tzara as “delirious strangeness in the spider of the hand vibrating quickly ascending towards the paroxysm of a mocking capriciously beautiful madness” (Tristan Tzara qtd. in Sawelson-Gorse 531), enabled the liberation of both poetry and dance from their visual, linguistic, and aesthetic sets of conventions (Hemus 2009, 69).

Not only the sound poems, but also the mask and concealing costumes had an enchanting influence on Taeuber’s moving body. Her costume was so tight, and so significantly restricted her movements (as seen too in Giannina Censi’s performance), that “for the whole night we could not get out of them”, recalled fellow dancer Mary Wigman (Mary Wigman qtd. in Sawelson-Gorse 530). The splendid influence of the mask on the performing Dada body, “demanding gestures, bordering on madness” (so beautifully described by Hugo Ball in his diary) was undeniable and integral to the effect of the performance.

In Taeuber’s case, the difficulties of dancing with the oppressive mask and costume echoed the struggle to break away from the stereotypes of femininity in a society that only demanded either her disintegration or her absence (Doutreligne and Stalpaert 540). As a “post-human” marionette, “not mechanical but quite derisory and in any case androgynous” (Bargues 100), Taeuber freed her own body from the constrictions of gender traditionally imposed on it. More specifically, her dancing body, abstract and genderless, resisted the graceful, romantic set of expectations projected on female performers (as cited by Richter). She refused to masquerade as a beautiful object of desire and neither did she passively disappear behind a mask (Doutreligne and Stalpaert 540). As such, her dancing with the anonymity of the mask and costume (and not only behind it), instigated a radically new mode of relating that sat in between male and female social codes (Ibid 538). A new way of relating that turned the gaze back on to the spectator in such a radical and direct way, that the same effect could never be achieved by the construction of the ‘female gaze’ within the Futurist feminist manifestos.

Fellow Dadaist Emmy Hennings was also performing in uncanny costumes and masks on the Dada stages. On the 14 July 1916, a few months after having founded the iconic performance venue Cabaret Voltaire, she performed three Dada dances in Zunfthaus zur Waag (Ingram 5): Fliegenfangen, Cauchemar and Festliche Verzweiflung (De Weerdt and Thurner 118). The similarities in the terminology and descriptions used by contemporaries in descriptions of Hennings’ and Taeuber’s performances are striking. Hennings’ costume consisted of “long, cut-out, golden hands on the curved arms” (Ball 64) and a mask by Marcel Janco (De Weerdt and Thurner 120). This “ghastly” (Suzanne Perrottet qtd. in De Weerdt and Thurner 121) mask, “made of cardboard, painted and glued” (Ball 64) was “wide open, the nose broad and in the wrong place” (ibid). Finally, the “only living part that could be seen were her feet, naked, all by themselves at the bottom” (Suzanne Perrottet qtd. in Kamenisch 20).

As was the case in Taeuber’s dance, Hennings’ movements were directly stimulated by the obstructing mask and costume: “The only thing suitable for this mask were clumsy, fumbling steps and some quick snatches and wide swings of the arms, accompanied by nervous, shrill music” (Ball 64). As a matter of fact, she “could do nothing else but clatter her feet and bend the whole thing like a chimney” (Suzanne Perrottet qtd. in De Weerdt and Thurner 121). In contrast to Taeuber’s “hundred-jointed body” and her nervous movements, one gets the sense that Hennings was moving less rhythmically and more expressively. Ball accentuated, above all, the “crouching position” from which Hennings was getting “straight up” to “move forward” (Ball 64). In addition to that, she turned “a few times to the left and to the right,” to “then slowly turn on her axis, and finally collapsing abruptly to return slowly to the first movement” (ibid). Adding up to this specific language of movement, she did “let out a cry, a cry…” (Suzanne Perrottet qtd. in Kamenisch 20).

However different her movements seemed to be from Taeuber’s dancing, Hennings’ performance, and more specifically her struggle with the obstructing mask and costume, testified to the difficult position as a female artist within Dadaism. That she valued the feminist cause of liberating women and their sexualities through art, was illustrated by the following statement by her Dada colleague Suzanne Perrottet:

I had the feeling that she knew life through and through and that I am still at the beginning of my life and have to fight for my ideas as a woman, as a free woman. That I am still inexperienced, and that she is already “through.” (quote transl. from German Baumberger Behrman 164)

Her performances were “an affront to the audience, and perturbed it quite as much as did the provocations of her male colleagues” (Hans Richter qtd. in Hemus 28). Her dance radically subverted the expectations of popular accomplished performance (ibid). Incorporating her background as a former vaudeville artist (performing in Munich and Berlin between 1912 and 1915), she combined this experience (as well as the gendered expectations of the audience in terms of objectifying the body) with the Dadaist body of language consisting of sound poems, a desire to shock, and a strong interest in geometrical costumes. Her hybrid performances made it almost impossible for spectators to recognize her biological gender (Ernst Thape and Martin Korol in Baumberger 150). Finally, Hennings consciously mimed the stereotypical imagery that was assigned to her: “she wasn’t merely a child, she knew how to play the child” (Hugo Ball qtd. in Hemus 20). In a similar way as was the case with Taeuber’s dance, Hennings playfully gazed back and radically challenged the problematic ‘male gaze’. In this, neither Taeuber nor Hennings sought emotional expression; rather, they aimed at questioning the body itself, as well as its position within the classification of the arts. Their abstract dances, in which they embodied Dadaist sound poetry, stood in opposition to the typologies of classical dance and its accepted standards of beauty as well as the Western fallacy of the subdivision of different art forms (Burmeister 22).

Conclusions

This article aimed to expose the different artistic strategies employed by female Futurists and Dadaists to contest the universal misogyny within the historical avant-gardes. This was done by outlining the (complex) context of the (terminology of the) ‘historical avant-gardes’, as well as the particular situation of Futurism and Dadaism participating in this greater cultural movement. Also, it was necessary to look at the main reasons why a great deal of female avant-garde artists was underexposed in art history for so long. Cultural-historical research reveals the unjust marginalization of numerous female pioneers of the historical avant-gardes through art history and how this was brought about in three ways. First of all, the instability of the economic context in which these artists were working forced them to combine their artistic practice with alternative sources of income (e.g., prostitution), as it also enabled them to work anonymously. Second, the widespread derogatory attitudes of male colleagues significantly contributed to their underexposure within art history. Finally, the rigid classification of the arts, and the subordinate position of dance within this, has rendered these artists silent and invisible in art history.

Female Futurist artists were contesting this process of marginalization in two significant ways. First of all, they introduced a ‘female gaze’ within the rather masculine medium of the manifesto. On the one hand, this allowed them to install their own right to exist within Futurism. On the other hand, it gave them a (verbal) stage on which to denounce their subordinate position within the movement. This was done through dealing with the stereotypical imagery of their time in a critical way, informed as it was by rigid gender constructions and gendered prejudices, as seen, for example, in Marinetti’s “contempt for women” (Marinetti 1909, 51). Versatile artists such as Mina Loy and Valentine de Saint-Point negotiated equality between the sexes in a critical way through their feminist manifestos. While de Saint-Point in her Manifesto of the Futurist Woman (1912) liberated gender from biological sex, introducing a feminist ideal of new (wo)man, Loy refused to accept the biological difference between the sexes by violently manipulating the female body itself (Feminist Manifesto, 1914).

Second, both female Futurists as well as Dadaists articulated the crisis of the binary pairing of male and female through genderplay. Inspired by the ideal of the ‘New woman’ and its widespread appearance in literature (e.g., Virgina Woolf’s Orlando), fashion (e.g., Ré Soupaults revolutionary ‘Transformation Dress’) and advertising (in printed press and billboards), these Futurist and Dadaist artists now turned to the body as the most daring and effective means of resisting female objectification. No longer functioning as the canvas onto which men could project their ideas of femininity (Coralie Malissard in Alison 165), they went further than installing a ‘female gaze’ as was done in feminist Futurist manifestos. Performing the bankruptcy of traditional gender constructions enabled female Futurist and Dadaist artists to drastically dismantle the rigid conventions that maintained the misogynist culture within the historical avant-gardes. Futurist Valentine de Saint-Point resisted the objectification of the male gaze in three ways. First of all, she performed her “woman warrior” through costumes that incorporated both feminine and masculine traits. Second, she liberated dance from the music which had previously dominated, extending this equality to body and reason as well as woman and man. Finally, de Saint-Point embodied her feminist ideas with the purpose of becoming them. By performing her idea through an “ideistic dance”, de Saint-Point succeeded in expressing the Futurist ideal of an anti-body while at the same time expressing the importance of her own presence on stage. Fellow Futurist Giannina Censi performed her ‘machine woman’ (incorporating the contradictions of nature, culture, machine and woman) and drew attention to the difficulties of this performance through being restricted by metal rings and screws.

This artistic strategy of genderplay matured in a similar way through the movement of Dadaism. In their iconic masked performances set to the rhythms of Dadaist sound poems, both Emmy Hennings and Sophie Taeuber succeeded in bringing the newly invented Dada language to a higher level. Their corporeal engagement with this new language surpassed the limitations of the recited sound poem. Even more, their embodied stuttering hinted at the dispensability of the verbality of the sound poem. This newly invented language was now hosted by a living body, discarding all logic. Moreover, their abstract and androgynous performances abolished traditional gender constructions. In dancing with the alienating mask and costume rather than dancing behind it, both Taeuber and Hennings denied the possibility of being confined to male stereotypes (Doutreligne and Stalpaert 538). They never masqueraded into beautiful objects of desire, rather they struggled (as illustrated by the oppressive masks and costumes they wore) (540) and instigated a radically new mode of relating that sat in between male and female social codes (538). A new way of relating that turned the gaze back on to the spectator in such a radical and direct way that the same effects could never be achieved by the construction of the ‘female gaze’ as was done within the Futurist feminist manifestos. Their performances contrasted with other contemporary performances such as Hugo Ball’s performance of the Magic Bishop. While Ball was paralyzed by struggling with his constricting costume and eventually had to be carried away, Taeuber resembled “a bird, a young lark, for example, lifting up to the sky as it took flight. The indescribable suppleness of her movements made you forget that her feet were keeping contact with the ground, all that remained was soaring and gliding” (Emmy Hennings in Schmidt 15). Similarly, Hennings stood up and moved forward: “she started from a crouching position, gets straight up and moves forward” (Ball 64). As such, both artists “instilled an image of resistance in their dancing with mask and costume. Their traumatized body does not end up as a paralyzed body. It is still a living body after all, and despite everything. Like a flower that wants to grow, despite the mud” (Doutreligne and Stalpaert 537).

This text first appeared in: DOCUMENTA, vol. 38, no. 2, 2020, pp. 32–62.

Works cited

Alison, Jane, and Coralie Malissard. Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy and the Avant-Garde. New York: Barbican, 2018.

Amrein, Ursula, and Christa Baumberger. Dada Performance & Programme. Zurich: Chronos Verlag, 2017.

Andrew, Nell. “Dada Dance: Sophie Taeuber’s Visceral Abstraction.” Art Journal 73:1 (2014): 12-29.

Ball, Hugo. Flight out of Time: A Dada Diary, ed. John Elderfield. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Balla, Giacomo, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà et al. “Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto (1910).” Futurism. An Anthology, eds. Christine Poggi, Lawrence Rainey et al. London: Yale University Press, 2009. 64-67.

Balla, Giacomo, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà et al. “Manifesto of the Futurist Painters (1910).” Futurism. An Anthology, eds. Christine Poggi, Lawrence Rainey et al. London: Yale University Press, 2009. 62-64.

Bargues, Cécile. “You will forget me. Some remarks on the dance and work of Sophie Taeuber.” Thoughtful Disobedience, eds. Sophie Orlando and Soni Boyce. Dijon: Les Presses du reel, 2017. 97-107.

Baumberger, Christa, and Nicola Behrmann. Emmy Hennings Dada. Zurich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2015.

Berghaus, Günter, and Valentine de Saint-Point. “Dance and the Futurist Woman: The work of Valentine de Saint-Point (1875-1953).” Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research 11:2 (1993): 27-42.

Boesch, Ina. Die Dada: Wie Frauen Dada prägten. Zurich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2015.

Bolliger, Hans, Guido Magnaguagno, and Raimund Meyer. Dada in Zürich. Zurich: Kunsthaus Zürich & Arche Verlag AG, Raabe + Vitali, 1985.

Bru, Sascha. The European Avant-Gardes, 1905-1935. A Portable Guide. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

Buckley, Cheryl. “Made in Patriarchy: Toward a Feminist Analysis of Women and Design.” Design Issues 3:2 (1986): 3-14.

Bürger, Peter. “Avant-Garde and Neo-Avant-Garde: An Attempt to Answer Certain Critics of Theory of the Avant-Garde.” New Literary History 41:4 (2010): 695-715.

Bürger, Peter. Theorie der Avantgarde, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1974.

Burt, Ramsay. The Male Dancer: Bodies, spectacle, sexualities. London: Routledge, 1995.

Conover, Roger, Mina Loy, and Jonathan Williams. The Last Lunar Beadeker. Highlands: Jargon Society. 1982.

Dech, Julia. Hannah Höch: Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser: Dada durch die letste weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch, 1989.

Deepwell, Katy. Women artists and modernism. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998.

Demos, T.J. “Circulations: In and Around Zurich Dada.” October 105 (2003): 147-158.

de Saint-Point, Valentine. “Manifesto of the Futurist Woman.” Futurism. An Anthology, eds. Christine Poggi, Lawrence Rainey et al. London: Yale University Press, 2009. 109-113.

De Weerdt, Mona, and Christina Thurner. “Tanz auf den Dada-Bühnen.” Dada Performance & Programme, eds. Ursula Amrein and Christa Baumberger. Zurich: Chronos Verlag, 2017. 107-126.

De Zegher, Catherine. Inside the visible: an elliptical traverse of 20th century art: in, of, and from the feminine. Ghent: La Chambre, 1996.

Doutreligne, Sophie, and Christel Stalpaert. “Performing with the masquerade: towards a corporeal reconstitution of Sophie Taeuber’s Dada performances.” Performance Philosophy 4:2 (2019): 528-545.

Enzensberger, Hans Magnus. “The Aporias of the Avant-Garde.” Modern Occasions, transl. John Simon, ed. Philip Rahv. New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1966. 73-101.

Felski, Rita. The Gender of Modernity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Foster, Hal. “Dada Mime.” October 105 (2003): 166-176.

Franko, Mark. Dancing Modernism / Performing Politics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995.

Futurluce, “The Vote for Women (1919).” Futurism. An Anthology, eds. Christine Poggi, Lawrence Rainey et al. London: Yale University Press, 2009. 251-253.

Hemus, Ruth. “Sex and the Cabaret: Dada’s Dancers.” Nordlit 21 (2007): 91-101.

Hemus, Ruth. Dada’s Women. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Ingram, Paul. “Songs, Anti-Symphonies and Sodomist Music: Dadaist Music in Zurich, Berlin and Paris.” Dada/Surrealism 21 (2017): 1-33.

Irigaray, Luce. This Sex Which Is Not One, transl. Catherine Porter. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985.

Jollos, Waldemar. “Vom Marionettentheater.” Das Werk. Schweizerische Zeitschrfit für Baukunst/Gewerbe/Malerei und Plastik 8 (1918): 128-132.

Jones, Amelia. Irrational Modernism: A Neurasthenic History of New York Dada. Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2004.

Kamenisch, Paula K. Mama’s of Dada: Women of the European Avant-Garde. South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2015.

Klöck, Anja. “Of Cyborg Technologies and Fascistized Mermaids: Giannina Censi’s “Aerodanze” in 1930s Italy.” Theatre Journal 51:4 (1999): 395-415.

Loy, Mina. “Aphorisms on Futurism.” The Last Lunar Beadeker, eds. Roger Conover and Jonathan Williams. Highlands: Jargon Society, 1982. 272-275.

Loy, Mina. “Feminist Manifesto.” The Last Lunar Beadeker, eds. Roger Conover and Jonathan Williams. Highlands: Jargon Society, 1982. 269-271.

Lusty, Natalya. “Sexing the Manifesto: Mina Loy, Feminism and Futurism.” Women: a cultural review 19:3 (2008): 245-260.

Mair, Roswitha. Handwerk und Avantgarde. Das Leben der Künstlerinn Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Berlin: Parthas Verlag, 2013.

Manning, Susan. Ecstasy and the Demon. The Dances of Mary Wigman. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. “Let’s murder the moonlight (1909).” Futurism. An Anthology, eds. Christine Poggi, Lawrence Rainey et al. London: Yale University Press, 2009. 54-61.

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. “Multiplied Man and the Reign of the Machine” (1915). Futurism. An Anthology, eds. Christine Poggi, Lawrence Rainey et al. London: Yale University Press, 2009. 89-92.

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature (1912).” Futurism. An Anthology, eds. Christine Poggi, Lawrence Rainey et al. London: Yale University Press, 2009. 119-124.

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (1909).” Futurism. An Anthology, eds. Christine Poggi, Lawrence Rainey et al. London: Yale University Press, 2009. 49-53.

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso, “The Manifesto of Futurist Dance (1917).” Futurism. An Anthology, eds. Christine Poggi, Lawrence Rainey et al. London: Yale University Press, 2009. 234-239.

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. “War, the only hygiene of the world (1911).” Futurism. An Anthology, eds. Christine Poggi, Lawrence Rainey et al. London: Yale University Press, 2009. 84-85.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”. Last accessed November 2020: https://www.asu.edu/courses/fm...

Orenstein, Gloria Feman. “Art history and the case for the women of Surrealism.” The Journal of General Education 27:1 (1975): 31-54.

Otto, Elizabeth, and Patrick Rössler. Bauhaus Women. A Global perspective. London: Herbert Press, 2019.

Pozorski, Aimee L. “Eugenicist Mistress & Ethnic Mother: Mina Loy and Futurism, 1913-1917.” MELUS 30:3 (2005): 41-69.

Rado, Lisa. The Modern Androgyne Imagination: A Failed Sublime. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000.

Rainey, Lawrence. “Introduction: F.T. Marinetti and the development of Futurism.” Futurism. An Anthology, eds. Christine Poggi, Lawrence Rainey et al. London: Yale University Press, 2009. 1-39.

Re, Lucia. “Mina Loy and the Quest for a Futurist Feminist Woman.” The European Legacy: Toward New Paradigms. 14:7 (2009): 799-819.

Re, Lucia. “Rosa Rosà and the Question of Gender in Wartime Futurism.” Italian Futurism 1909-1944. Reconstructing the Universe, ed. Vivian Greene. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications. 2014. 184-190.

Salaris, Claudia. “The Invention of the Programmatic Avant-Garde.” Italian Futurism 1909-1944. Reconstructing the Universe, ed. Vivian Greene. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications. 2014. 22-49.

Satin, Leslie. “Valentine de Saint-Point.” Dance Research Journal 22:1 (1990): 1-12.

Sawelson-Gorse, Naomi. Women in Dada. Essays on sex, gender and identity. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1998.

Schmidt, Georg. Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Basel: Holbein Verlag, 1948.

Schmutz, Thomas. Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Today is Tomorrow. Aarau: Argauer Kunsthaus, 2014.

Sica, Paula. Futurist women. Florence, Feminism and the New Sciences. UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, 154.

Veroli, Patrizia. “Futurism and Dance.” Italian Futurism 1909-1944. Reconstructing the Universe, ed. Vivian Greene. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications. 2014. 227-234.

With support of the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO)